Why Study the Biblical Languages?

Author: Davy Ellison

In recent weeks there has been much discussion in the media concerning the study of foreign languages. Specifically the confirmation that oral exams will be dropped from GCSE and A Level language courses in 2022. For some this is welcome news. I can recollect completing some of my French GCSE oral exam in English—so this would have been welcome news for me. For others it is a travesty.

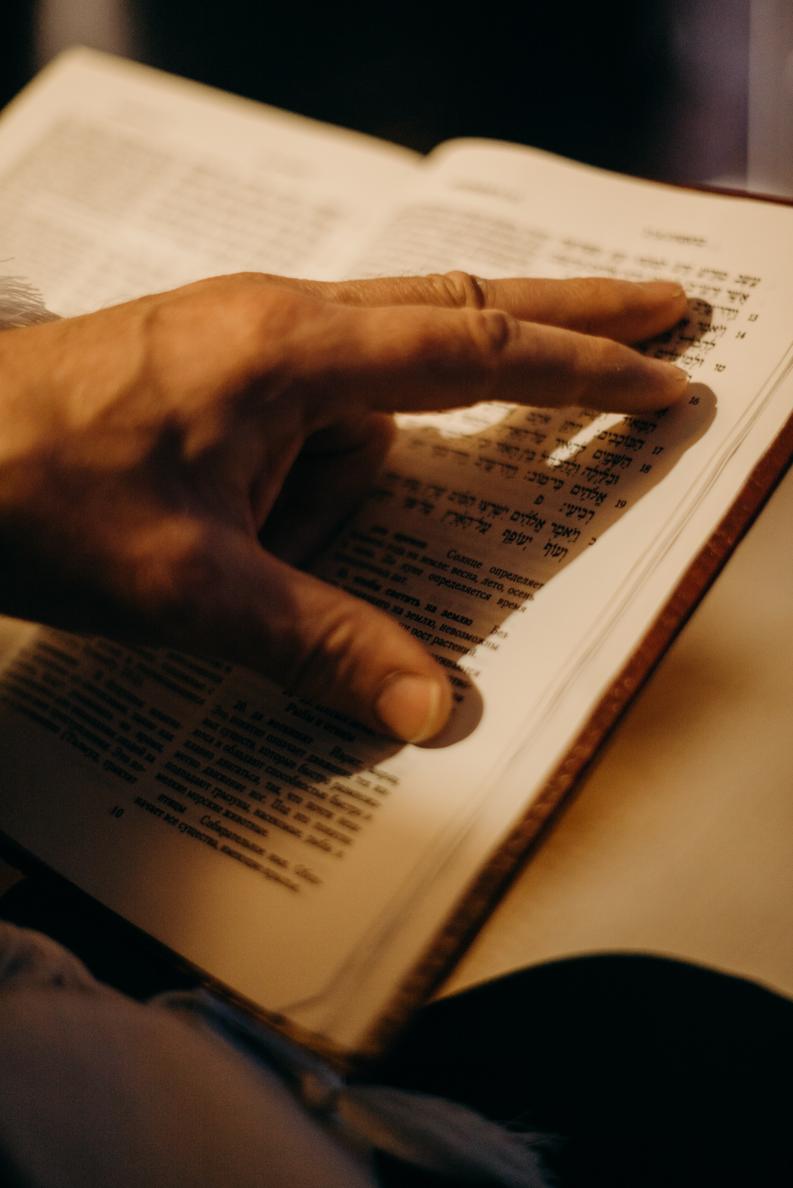

Whether or not they are a linguist, every student who enters the Preparation for Ministry course at the College is introduced to the biblical languages. Why? This is the question I want to answer today. While there are many answers to this question, I want to offer four brief reasons for studying the biblical languages.

It Increases Awareness

Something is always lost in translation. This fact is the perennial issue in translation work. While no English translation is perfect, most of them are accurate and readable. The issue is that there is always a choice to be made.

From the outset the translator(s) must decide whether they will operate a formal equivalence philosophy (translate word-by-word) or a dynamic equivalence philosophy (translate phrase-by-phrase/meaning). Either the translator(s) must sacrifice the flow of the English language or the literalness of their translation. After this decision, many more are necessary on which English word or phrase best captures the impetus of a given Greek or Hebrew (or Aramaic) term.

If we know the biblical languages we have an ability to weigh up the translator’s decision on the basis of our own knowledge and ability to read the text in its original language. Indeed, we may come to find that we disagree with a particular translation choice. But such an ability is restricted to those who know the biblical languages because they have studied them. Studying the biblical languages increases awareness.

It Introduces Intimacy

The ability to read the original language, instead of relying on a translation or a commentary, moves the reader closer to the biblical text. This introduces an intimacy. In becoming intimate with the biblical text our understanding and discernment grow. The primary benefit of increased intimacy is that we are changed. God’s word is living and active (Hebrews 4:12), and profitable in all manner of ways (2 Timothy 3:16). As a result, intimacy with the text changes the reader under the influence of the Spirit. But a secondary benefit is that a student of the biblical languages is better equipped to assess the latest Bible translation, the emerging theological trend and the novel developments in Christian culture. Instead of relying on someone else’s take, the student of biblical languages can check it out for themselves.

It Fosters Confidence

Increased awareness and intimacy give rise to confidence. Familiarity with the biblical languages offers confidence in preaching and teaching the truths of Scripture. Instead of relying on commentators or scholars to explain things, the student of biblical languages should develop an ability to explain things for others. To be able to speak with first-hand knowledge of issues offers a confidence that cannot be found in passing on second-hand opinions.

Equally, however, this should be a humble confidence. Engaging the Bible in its original languages is another reminder of how little we know and how much work it takes to grow in knowledge and understanding. It is not therefore a confidence in ourselves that studying the biblical languages should foster, but a confidence in the book we proclaim.

It Cultivates the Right Kind of Critics

No-one wants to cultivate critics!

I disagree. I want to cultivate critics (or at least see them cultivated)—but the right kind of critics. True, the church is in vital need of pastors, missionaries, Bible teachers, elders, deacons, ministry leaders, and evangelists. However, the church is also in vital need textual critics.

Textual critics are the people who seek out ancient manuscripts, spend endless hours reading and reproducing them and finally deciding which variant readings are the best option. It is the textual critic who can offer the latest information on ancient manuscripts to inform ever better Bible translations. But this skill requires a deeply intimate knowledge and understanding of the biblical languages, among many other skills. Textual criticism is not a glamourous career, but it is ever so important for the church. Textual critics ensure access to and comprehension of the most accurate manuscripts. They are thus vital to maintaining excellence in Bible translation.

Conclusion: For the Gospel

In 1524 Martin Luther, father of the Protestant Reformation, charged his contemporaries with these words:

Let us be sure of this: we will not long preserve the gospel without the languages. The languages are the sheath in which this sword of the spirit [Eph. 6:17] is contained; they are the casket in which this jewel is enshrined; they are the vessel in which this wine is held; they are the larder in which this food is stored. . . . If through our neglect we let the languages go (which God forbid!), we shall . . . lose the gospel.

Humanly speaking, so Luther argued, the hope of the gospel is bound up in churchmen maintaining an aptitude for the biblical languages. Why do we introduce all of our Preparation for Ministry students to the biblical languages? Because we are passionate about the gospel.

For further reflections see Bitzer was a Banker! by John Piper and The Profit of Employing the Biblical Languages: Scriptural and Historical Reflections by Jason DeRouchie.